Today I want to talk about an important idea when it comes to lifting weights: progress! Everyone wants to see a return on their hard work and lifting weights is no exception. But as a beginner, what should you expect from your program? In short, how often should you expect to make a demonstrable progress.

The Novice

Using the term “novice” is a hot take right now in the S&C world. In part, because it’s difficult to pin down when someone is a novice and when someone isn’t a novice. Similarly to other endeavors, new weightlifters / powerlifters / strength trainees should expect to see regular progress or gains. But how often? What if you don’t see progress every session, are you still a novice? Furthermore, do you just need to “sack up” and put more weight on the bar or is having an “off day” a real thing? You can already see some of the issues with labeling strength trainees.

A framework that I have used historically can be found in 2nd edition of Programming to Win, written by Izzy Narvaez. If you haven’t read any of his work, I would recommend it. The framework he lays out looks like this:

- Novice – an that that does not require manipulation of training variables or periods of training dedicated to specific qualities.

- Intermediate – an athlete that does require manipulation of training variables but does not require periods dedicated to specific qualities.

- Advanced – an athlete that requires manipulation of training variables and periods of time dedicated to specific qualities.

This is a nice framework as it aims to speak to the lifter’s needs rather than an arbitrary timeline for progress. Of course, using the framework above will generate expected timelines but the classification system is more about what type of programming should be used to generate progress. As you might expect, complexity increases as the lifer moves from novice to advanced.

You’re (probably) Not an Advanced Athlete

At the risk of sounding like a jerk, you probably needn’t worry about the classification above. At least not beyond the intermediate level of training. Why? Simple, most of the people going to the gym aren’t solely interested in lifting heavier weights. Instead, they want to get stronger, look better naked, decrease their back pain, and be in good enough shape to go on their annual ski trip. Furthermore, they have lives that aren’t centered around training. They aren’t living in a basement, eating moms home cooking and attempting to put on 25lbs just to see their bench climb to 315. All this is to say, your programming can probably be kept reasonably simple.

Simple is good! Progress is abundant!

Sample (simple) Programming

Using our framework above, our beginner programming might look like this:

| WK 1 / Day 1 | Week 1 / Day 2 | Week 1 / Day 3 |

| Squat 5 x 3 | Squat 5 x 3 | Squat 5 x 3 |

| Bench Press 5 x 3 | Press 5 x 3 | Bench Press 5 x 3 |

| Deadlift 5 x 1 | Options (chins, pull downs, power cleans) | Deadlift 5 x 1 |

| WK 2 / Day 1 | WK 2 / Day 2 | WK 2 / Day 3 |

| Squat 5 x 3 | Squat 5 x 3 | Squat 5 x 3 |

| Press 5 x 3 | Bench 5 x 3 | Press 5 x 3 |

| Deadlift 5 x 1 | Options (chins, pull downs, power cleans) | Deadlift 5 x 1 |

This would be a useful way to start training in the gym. The athlete is prioritizing some nice, compound movements and seeing them often. This (in theory) will lead to quick(er) technical proficiency and strength gains.

Additionally, we would expect the athlete to attempt to add some weight each time they train. Fob obvious reasons this won’t last forever… but it will last for a while.

More Training = More Complexity

Along the way we’d like to make some adjustments for our athlete above. They might look like any of the following:

- a light day

- back off sets

- exercise selection changes (pause squat instead of squat)

There is nothing magical about these adjustments, nor do they need to occur in any special order. Ideally, the trainee will be lifting for a long (long) time so there’s no need to crush them with some arbitrary adjustment progression. Instead, we’ll keep what’s useful and work WITH the athlete to keep finetuning the program to suit their needs / goals.

Fatigue Management 101

As the athlete grows in his/her strength, the stress needed to generate progress will increase. As will the athlete’s ability to generate said stress. As coaches, we’re always trying to maximize fitness (strength in this case), while minimizing fatigue. That being said, you can never really achieve one without the other to some extent. Smart programming can then be described as programming that attempts to intelligently achieve this balance in favor of the athlete.

What am I talking about? Periodization is a (somewhat) organized form of fatigue management. In essence, you are creating peaks and valleys in your program design. Said another way, some hard days, some light days, and a bunch of days in between. Periodization attempts to keep the needed increased stress manageable.

Here are some ways we might incorporate basic periodization into our simple program design:

Option 1: Heavy / Light / Medium Framework

This set up is fantastic, we are very grateful for Bill Starr’s simple program design. The H/L/M framework allows the athlete to train a lift at a high frequency whilst attempting to manage fatigue. It looks like this:

- Mon (heavy) Squat 5 x 1 @82.5%

- Wed (light) Squat 5 x 2 @ 70%

- Fri (medium) Squat 5 x 4 @ 75%

The H/L/M is a great way to introduce some basic periodization into beginner programming.

Option 2: Cycling

We love this option at the gym and find that it works great for the vast majority of folks we work with. Some benefits include:

- higher variety

- regular PRs

- fatigue managment

Higher variety can be achieved by simply cycling your intensity exercises. Let’s say on Mondays we plan to squat something heavy. It could look like this:

- WK1 – low bar squat 3×1 @9 effort

- WK2 – pause squat 3×1 @9 effort

- WK3 – front squat 3×1 @9 effort

- WK4 – low bar squat 2×1 @9 effort

- WK5 – pause squat 2×1 @9 effort

- WK6 – front squat 2×1 @9 effort

As you might expect, weeks 7-9 would focus on heavy single attempts. This is a really fun way to organize training and also really reduced the soreness / accommodation (backslide) that would result from continually trying to perform the same exercise in a heavy manner repeatedly.

What about cycling the reps? Yep, that works great too! It would look like this:

- WK 1 – squat x 8 reps

- WK 2 – squat x 5 reps

- WK 3 – squat x 2 reps

- WK 4 – squat x 8 reps

- WK 5 – squat x 5 reps

- WK 6 – squat x 2 reps

Each cycle the athlete attempts to “beat” his previous numbers. Again, this is a fun way to train as it allows for regular PRs (theoretically) whilst minimizing the negative aspects of repeatedly heavy work with the same exercise.

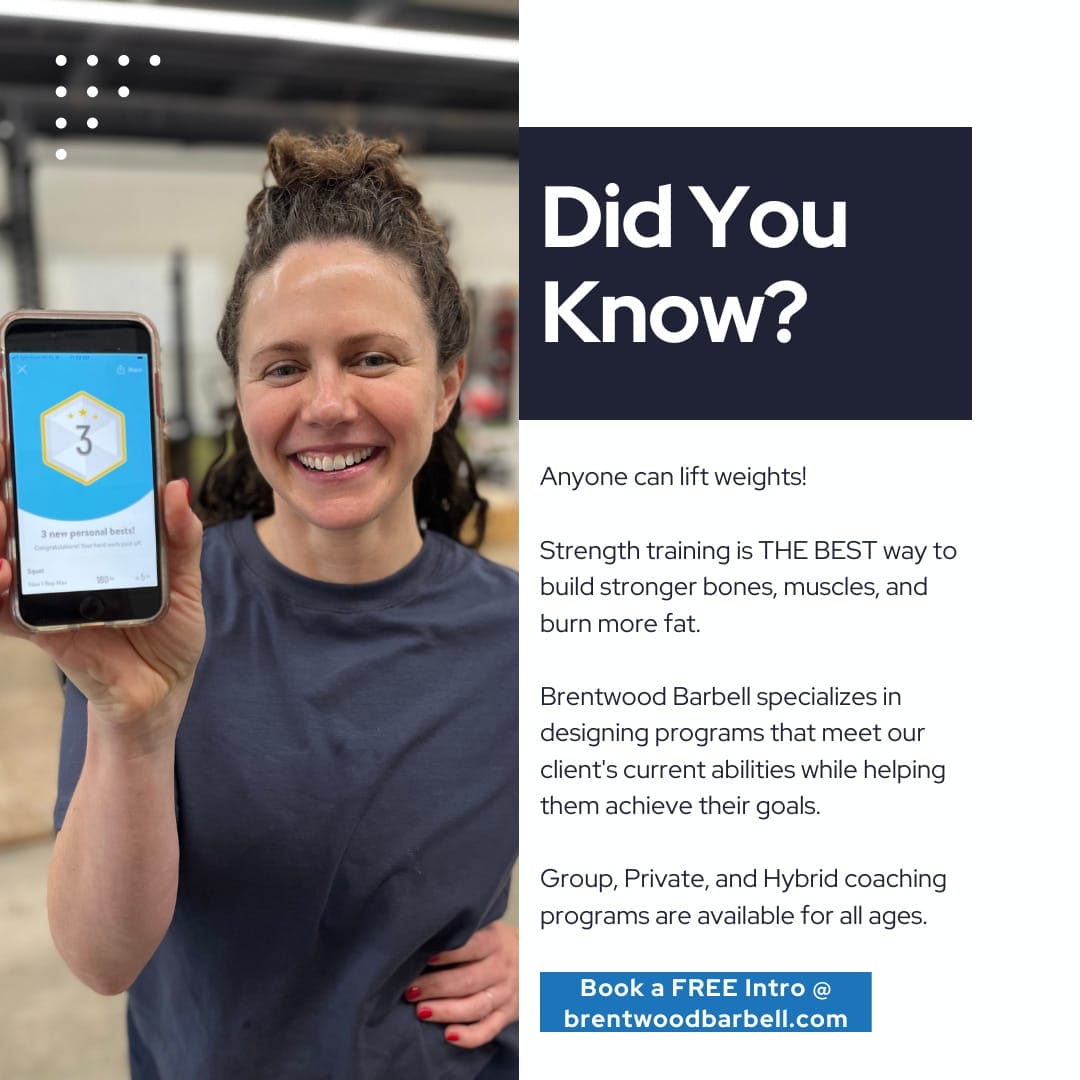

Is Rate of Progress Really that Important?

I’ve talked at length about Bright Spots (small, regular wins) in the past and that’s exactly what PRs are all about. You’re being consistently rewarded for your hard work. Here’s an example. Let’s take 2 athletes, each squat 200lbs for 1 rep. Now we’re going to train them for 12 weeks.

- lifter A hits a 60lb PR in week 12 but otherwise trains using non PR weights

- lifter B hits a 5lb PR each week

Both lifters finish with a squat PR of 260 but lifter B is happier. Lifter B also sees how his training is going each week. He gets a chance to monitor and change his program more closely to his actual capacity vs. lifter A. Lifter A gets to train for 12 weeks hoping a PR is at the end of the rainbow. It might be, it might not be.

As is common with January, everyone is thinking about goals and stuff they’d like to achieve. Looking at your projected Rate of Progress is one way to make sure you get there. Don’t wait until March to see how things are going. Task yourself with regular wins along the way, you’ll be glad you did.

If you need help, we got you: Book a Meeting

Otherwise, go destroy the week!

Talk soon,

James