I remember reading a book years ago from Pavel. The book was the Professional Power to the People. The book claims you can add 100s of pounds to your squat, bench press, and deadlift total using the programming inside. Perhaps.

I’m still working on the hundreds of pounds more on my total but the book did offer some great insight. One of the key takeaways for me at the time was the idea of “specialized variety”. Pavel describes exercises that fall under the term “specialized variety” to be those closely related to the exercise you’re aiming to get better at. In this case, we are talking about the competition squat, bench press, and deadlift.

How does this work?

One idea is that the athlete has to overcome the novelty of the special exercise and as he/she does so, this new found coordination will carryover to their parent exercise.

Another idea is that some specialized variety exercises might be harder than the parent exercise, making any gains in that exercise likely to carry over the easier, parent exercise.

Additionally, some of these exercises can be loaded much heavier than the parent exercise, making the smaller weights used in the parent exercise easier to handle.

But what about folks that don’t care about their total? What about folks that exercise to get stronger, feel better, lose some body fat, and manage their blood pressure? Does someone with high blood pressure need to care about this stuff? Perhaps.

In the Beginning

When I first found barbell training and coaching my programming was typical. It was highly specific to a few exercises. Mostly, I had folks low bar squat, touch n go bench press, overhead press, and conventional deadlift. If you’re thinking this sounds a lot like the recommendations put forth in the book Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training, 3rd Edition, it’s because that’s exactly what I was doing. At least to the best of my ability.

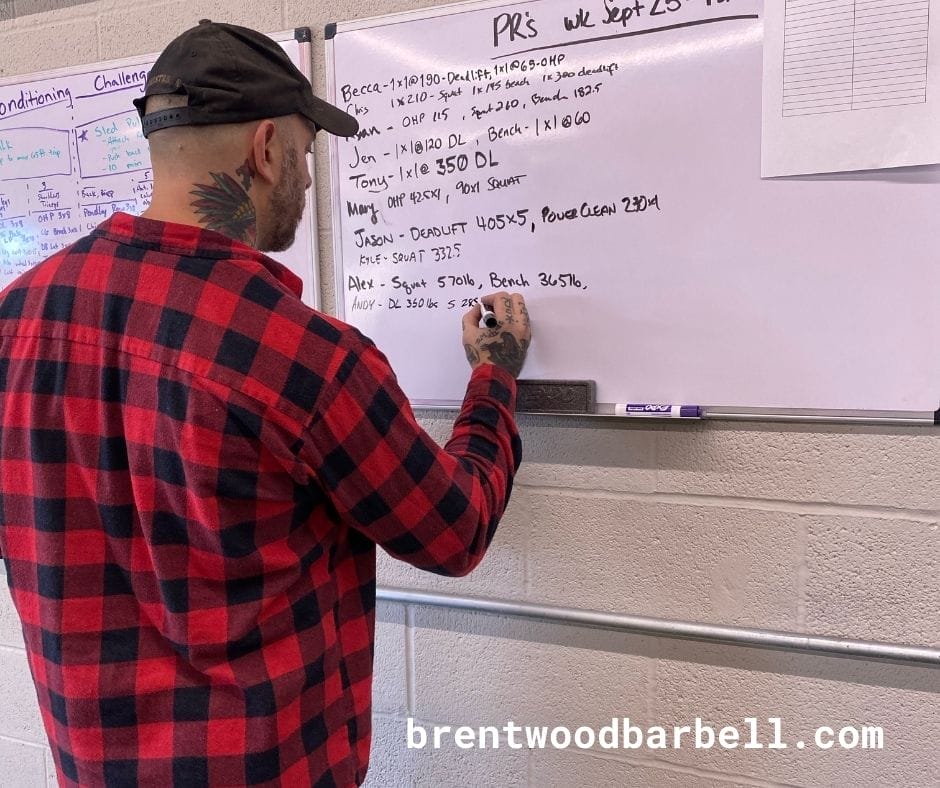

Beginner programs at our gym still look a lot like that simple set up with a few accessory items layered in. Our programming changes the most as an athlete becomes more skilled or advanced. Once way we do this is by exposing him/her to variations of the “parent” barbell exercises noted above. I use air quotes because those exercises are only parent exercises to someone looking to compete in barbell strength sports like powerlifting. Most people wouldn’t place any special fondness on those specific exercises, nor should they.

Still, our programming revolves around simple, basic barbell exercises and close variations as these tend to be the best exercises to get folks generally strong, move a good deal of weight with, provide a fun / skill development aspect to exercise, and carry-over to life outside the gym.

Today, I want to talk about an exercise that falls under this category of “specialized variety” that we find ourselves using time and time again with folks. The box squat!

What is a Box Squat?

A box squat is an exercise in which the athlete moves from a standing position to sitting down on a box. It’s a lot like sitting in a chair. We usually have some particulars in how the athlete will maintain some tension in the bottom, their shin angle, and the amount of forward lean we want but it’s basically sitting in a chair with a barbell on your back.

You might be thinking, why in the hell would anyone want to do that? In order to understand that, you will need to first understand that squatting (in general) is an incredibly valuable thing to do in the gym. Squatting builds a lot of muscle mass, burns a lot of body fat, builds healthy resilient joints (hips, knees, and low backs), and generally provides the user with a sense of accomplishment when their done.

From there, box squatting becomes important in the sense that everyone should want to squat at the gym but not everyone will be able to squat. Enter the box squat!

Let’s look at a few reason you might want to add this exercise to your program.

Reason #1: Easier Learning Curve

The box squat is just one of those exercises that people get right. It’s sort of like the trap (hex) bar deadlift in that way. Maybe its because removing the bottom “free” position in the traditional squat allows the athlete to focus on other elements like foot placement, bar path, or breathing?

The box squat removes all chance of falling over. That’s useful of course.

During our Barbell Intro Program, we may initially start an athlete free squatting but find that it’s taking too much time to see any headway. Usually, in those circumstances, we’ll opt for the box squat so they can start training today. This is particularly true if the the athlete has no interest in barbell strength sports at that time. So… about 99% of everyone we work with.

Time is money and we want our athletes training productively as soon as possible.

Reason #2: Improves Balance & Coordination

A lot of athletes struggle with proper squat depth. Many times, people will say “I’m not flexible enough to squat to depth”. Most of the time, this simply isn’t the case. More often than not, the barbell-lifter system is out of balance. The appearance of limited mobility is simply to keep from falling over. The athlete is likely on his/her toes or heels too much. Subsequently, the bar path does not ride vertically over the midfoot position while he/she squats down.

Once the athlete understands balance and bar path, their depth increases immediately. The Box squat can be really helpful in these situations by allowing the athlete to focus on the bottom position and finding their “mid foot” while not falling over. If “regular” squatting is important, the box squat can be an excellent teaching in getting the athlete there.

Reason #3: Speed and Acceleration

There is nothing keeping an athlete or coach from focusing on acceleration during a free / traditional squat, it just comes more natural when using a box squat. By breaking up the concentric / eccentric portions of the exercise, the athlete can place a lot of emphasis on standing up quickly if he/she is doing so from a dead-stop position. The athlete can focus on positioning during the eccentric (down) portion, come to a complete stop on the box, and then focus on exploding off the box.

This combination of breaking up the eccentric / concentric phases of the exercise while putting maximal effort into standing up can be potentially enhanced with the use of accommodating resistance (bands and chains). By adding bands / chains, the barbell gets heavier as the athlete stands up, making it more natural to push all the way through the movement. Bands and chains are not required to build acceleration but it does seem to help.

Reason #4: Improving Orthopedic Limitations

Being a physical therapist, I get my share of injured folks coming into the gym. Exercises like the box squat can be an incredibly effective tool in the coaching toolbox. As I mentioned above, we want our athletes training productively ASAP, the box squat can help.

Lower Quarter Pain During Squatting

If we know an athlete experiences knee or hip pain at a particular depth of the squat, we can easily set the box a bit higher and train through their productive range of motion. Given that pain tends to decrease with appropriate movement selection and dosage, we often end up lowering the box over some number of weeks or months.

During that time, the athlete may or may not be specifically addressing the hip/knee symptoms. Either way, using the box squat, will allow the athlete to safely, and effectively exercise during this time.

The box squat is a great tool that every athlete, general population gym-goer, and powerlifter should have in their toolbox. Want to know more about how the box squat might be a key part of the program you need to meet your goals? Go ahead and Book a Meeting with one of our coaches and we’ll get started.

Talk soon,

James