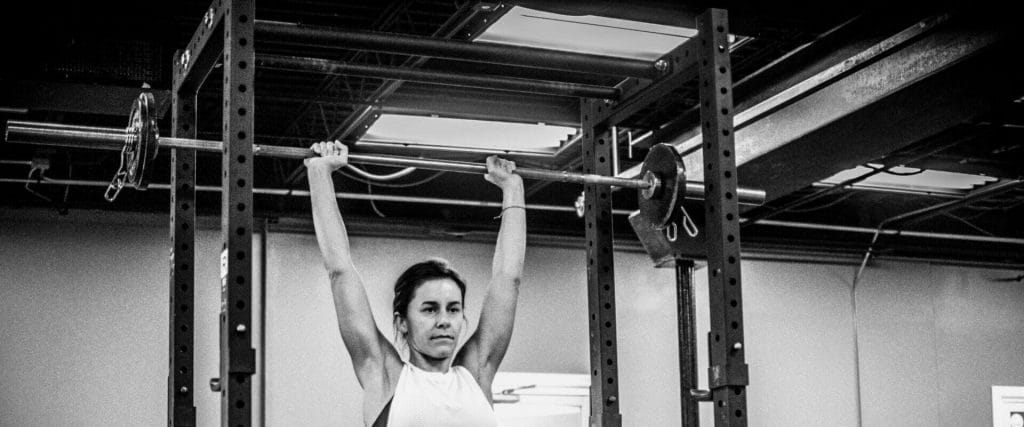

The vast majority of conversations I’ve had with other health professionals around the topics of shoulder health, overhead pressing, and rehabilitation of the shoulder over the last 10 years have one thing in common. Very few of them are recommending the bench or the overhead press in their plans.

I’m not sure why this is, I’ve always had tremendous success utilizing bench and overhead press variations in shoulder-centric programming. Today, I thought I’d run through some thoughts on these topics. Keep in mind, this is not specific recommendations for your circumstances, I don’t know you. I do understand the shoulder, and how it’s used (and not used) in daily life but a reasonable evaluation should always precede a rehab/exercise plan.

Pain, an Updated Model

Historically, the physical therapist approach to pain has been largely biomechanical in nature. This model tells us the body receives a noxious stimulus (tissue injury), the tissue sends a message up to your brain, your brain responds accordingly by ramping up the pain sensation in order to change your immediate behavior. This is thought to be protective in nature. This view also relied on the notion that “pain fibers and receptors” sent this information, minimizing the complexity of a pain experience and the brain’s response.

In recent years the view on pain… particularly chronic pain, has evolved to include psychological and social factors. The traditional biomechanical component of pain is still certainly very relevant but these additions create a more holistic view of the “pain experience”. We know the other factors are vital to effective rehabilitation. This newer, holistic view is known as the Biopsychosocial Model of pain.

Additionally, further examination of the Fear-Avoidance Model suggests that as therapists and coaches, we have a tremendously important role to play, not only in rehabilitation, but also in life outside of the gym. An oversimplification of the model tells us, after an injury, patients will typically choose to move “toward” or “away” from their pain experience. Often, patients that move “toward” their pain experience have better results. This information doesn’t discount the biomechanical component of their pain experience, it only states that there are other relevant factors that impact success. The classic example here would be someone tweaking their back raking leaves in the yard. Upon coming into the gym, I inform them we’re going to begin their program with rack pulls. The patient has a few options in their response:

- Ok, cool

- Nope, not doing it

- How about not right now but maybe in a couple weeks

All are valid from the patient’s perspective. What we want to avoid, is scenario #2, where the patient says “nope, not doing it”. While that might be perfectly reasonable in the short term, over time, we want to get the patient to a place where they trust using their back.

Historically, my experience as a coach/therapist has been the sooner we get moving in a direction “toward” the scary thing, the better the long term outcome.

The Brentwood Barbell Approach

When I was a therapist working in an outpatient orthopedic clinic, we saw a lot of shoulder, knee, hip, and low back injuries. Some of these were post-surgical, every now and then I’d see some pre-surgical, but most of the time I saw folks that had pain for no identifiable reason. They just hurt.

When an athlete comes in with an injury or limitation, we have a few general goals we want to accomplish with them.

- desensitize the area (make it hurt less)

- increase functional (useful) range of motion

- increase tissue strength surrounding the joint

Goal #1: Desensitize the Area

Many PTs get bogged down in the weeds here. Instead of thinking “how can we improve shoulder function (as it matters to the patient) they often fall down biomechanical rabbit holes like the “trap-serratus force couple”, “infraspinatus weakness”, or an “internal rotation deficit”. The assumption being that these areas are only worked appropriately with very specific, physical therapy, isolation-type exercises. If you’ve been to PT, you know what I’m talking about:

- banded shoulder external rotations

- bird dog planks

- glute bridges

- posterior capsule stretching

It isn’t that there isn’t a time and place for any/all of these, it’s just that they don’t matter to the patient. They don’t look like what he/she is going to be returning to. That stuff looks like putting things in a cabinet, pushing a wheelbarrow full of potting soil, running up and down their steps 12x per day.

We often use very light barbell exercises, depending on the client. Why? We know we eventually want to go there so why not get started ASAP? The desensitization phase must be short term, we have to move on to more challenging exercises to actually make a meaningful change.

Goal #2: Increasing Functional Range of Motion

Generally speaking, we don’t stretch. I’m not saying we don’t ever but we don’t make it a point to include stretching when we’re working with an athlete or client. We have better things to do with our time. Sometimes clients will ask if they can do some stretching, that’s usually fine (with some direction) but we will usually put it very low on the priority list.

We do aim to improve mobility of the shoulder joint, however. I say mobility as we’re going to work the patient through his/her range of motion with a tolerable load and this will change the mobility of all the tissues involved (muscle, tendon, joint capsule, etc.). So it’s not so much about pushing a specific muscle to it’s end point here.

We would begin their program with variations of the bench and the press. Most likely, the loads we’re going to be working with will be much lighter than what they’re used to training with. This is ok, it will give the athlete an opportunity to calm down and establish a baseline. Examples here might include pin variations for both the bench and the press. We’ve also used high incline pressing in the event that pressing is not tolerable and we’ve also used low incline benching if/when the flat bench is not tolerable. The importance of starting “light” cannot be overstated.

Over time, we aim to “lower the pins”. That is, have the client take the barbell through a progressive increase in functional range of motion. Again, the weight is often pretty light here. We want enough to elicit a response, the response being maintained increased range of motion, but not so much as to piss the area off. Of course, some irritation is to be expected but we should see a return to baseline withing a couple of days.

In addition to our barbell exercises, we may also strategically pick a few isolation exercise to compliment the barbell work. These are not necessarily based on specific muscles (but sometimes they are). Most of the time, we’re simply looking at the shoulder from a quadrant perspective. We want exercises that ask the client to move into:

- extension

- abduction

- adduction

- flexion

These might look like lateral raises, pull downs, rear delt raises, face pulls, trap 3 raises, etc. We’re not necessarily expecting “that one muscle” to dramatically change the client’s situation, rather we’re just working the shoulder through it’s entire range of possibilities. We would expect these to increase over time.

Goal #3: Strength Training

First, very few PTs know what to do in the weight room regarding legitimate strength work. They aren’t able to coach strength exercises like presses, squats, and pulls. Because their “coaching” knowledge is limited, they choose exercises that don’t require coaching. Stuff like short-arc quads, banded rotator cuff exercises, and glute bridges. Let’s not forget the bird-dogs… elite core strengthening!

The obvious problem here is that getting strong requires enough stress to drive the adaptation of strength. If strength is important, then shouldn’t we do what we know works best to get folks stronger? This doesn’t work very well with isolation exercises. Sure, you can progress them, to a point, but how heavy can a lateral raise be?

Enter, basic barbell exercises and progressive loading. Using exercises like benches, presses, and big upper body pulls like lat pulls and DB rows allows the client to work hard enough to actually begin creating the stress needed for the desired adaptation, i.e., strength!

The good news, we’ve been doing benches and presses since the beginning. We’ve worked the pins down to full, or nearly full, range of motion. Now we begin focusing on adding load. Slowly but sure, the weight on the bar goes up. Often, this will ebb and flow but the trend is heavier weights over time.

Why do you care? Because being better at the bench and the press makes you ready to do the stuff in your life / sport that you’re actually going to be doing. The transference is high! This is what you’re actually paying for, not to learn more about the influence the upper trapezius has on shoulder elevation.

Who Should be Using Barbells to Fix Their S**t?

Pretty much everyone. We don’t often see post-surgical folks as often tissues are still very much in the healing phase. That’s actually a great time for some traditional PT work that we’ve seemingly been so dismissive of up to this point. As I stated above, there is a time and place for some of those discussions and exercises, it just needs to lead somewhere more challenging.

If you’re letting a previous injury or currently achy shoulder keep you out of the gym, it doesn’t have to be that way. Book a Call with one of our coaches to learn more about how barbell strength training can be the answer you’ve been looking for.

Talk soon,

James